Nour Ballouk is a young, emerging Lebanese artist who in 2014-2015 created a series of digital artworks titled ARAB SPRING DANCE. Printed on large sheets of translucent plexiglass that give them luminosity--and a suggestion perhaps of iconic stained glass windows--these works are all variations of a brilliant and provocative artistic juxtaposition: ghostly images of Orientalist dancers overlaying photos of the destruction that has been the result of the ongoing wars and occupations of Gaza, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria.

|

| Nour Ballouk, Beirut April 2015 |

From my first viewing of these images, I felt that Ballouk had succeeded in producing true symbols whose meaning cannot be exhaustively explained in words, not even by a statement from the artist herself.

The “Arab Spring” is a journalistic label used to describe a remarkable series of populist uprisings against oppressive leaders and governments that, according to a Wikipedia time-line, exploded like a string of firecrackers, spreading from Tunisia in 2010 to Algeria, Lebanon, Jordan, Oman, Mauritania, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Djibouti, Morocco, Sudan, Palestine, Iraq, Bahrain, Libia, Kuwait, the Western Sahara, Iranian Khuzestan to the borders of Israel. But after the early euphoria of these people's rebellions, there has been a settling back into versions of business-as-usual and on-going conflicts. It is not my purpose here to offer a political analysis of why these events have taken place or the course they have taken. There are endless numbers of back-stories, spun opinions, and distortions to sift through. The oppressors in an Orwellian world wear many different masks and even layers of masks. But one thing is obvious: in these wars and occupations innocent people have been hurt and ancient structures that are memory holders for all of mankind are being destroyed.

|

| Syrian Rhapsody, The Arab Spring series, 2014 |

According to Nour, the piece titled “Syrian Rhapsody” was the one that started the whole series off. Prancing on the balls of her feet, the veiled dancer arches skyward in front of a photo of the Khalid abin Walid Mosque's partially destroyed mausoleum in the AL-Khalididya. The artist has said of the Arab Spring Dance series:

“It is a way to honor these Arab cities charged with history, that are evidence of a great and ancient civilization now afflicted by destruction and death. Cities that carry in them deep sorrows as ancient as the old churches of Syria, the shrines in Iraq, and the temples of Luxor...”

|

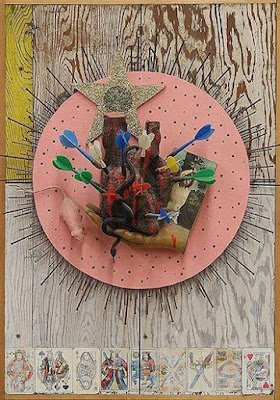

| Torments, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

In this poignant lament, and in the production of this series, Nour clings to the right of ecstasy rather than a crushing defeat and depression. In the summer of 2006, only recently graduated from the Lebanese University in Beirut with a B.A. in arts, she was one of several Lebanese artists whose art and studios were damaged or destroyed in an Israeli attack on several areas of Lebanon .

|

| Ballouk's workshop, Lebanon_Nabatieh 2006 - AFP photo by Anwar Amro |

|

| Ballouk's Home destroyed, Lebanon_Nabatieh 2006 - AFP photo by Anwar Amro |

But in September, the artists affected by the attack rallied together and under tents atop the rubble of bombed out buildings exhibited their war-damaged work. She said:

“The Israeli destruction of my art caused a temporary setback, but it didn't break my spirit as a human being or as an artist. I will continue to create and paint.”

Eight years later she came out with Arab Spring Dance.

|

| On the Wire, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

Some historians have suggested that the appropriation of the image of the dancing harem girl, the Orientalist dancer costumed in translucent fabric and draped with strings of pearls, was somehow part of the effort by the Western powers to dominate and colonize those lands and those peoples, something that was undoubtedly fated to happen when the industrialized infrastructures (and military forces) of the West came to be powered by oil.

|

| Rituals, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

According to Virginia Keft-Kennedy, the version of the Orientalist dancer known as the “belly dancer” was introduced to the West at the series of World Exhibitions in the late 1800s, and used for erotic titillation at the Fairs. In the late 19th and early 20th Century, Western women began to emulate, appropriate and transform the dances of the Middle East as these expressions became a part of feminist politics. And as I write this today from the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California I am witness to the enormous popularity of Belly Dance as a part of a New Age, neo-pagan feminist culture here. For better or worse, we are now all part of an electronically-connected, increasingly globalized culture in which cultural traditions, sacred teachings, art, and products are being exported, imported and mixed into new amalgams and hybrids. One reading of these juxtapositions in Arab Spring Dance is obviously that of a savage irony. Among the images of dancers used by Ballouk is that of Princess Banu, a contemporary Turkish belly dancer who had performed for heads of state like Hosni Mubarak and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, both of whom were ousted during the Arab Spring uprisings.

|

| Surreal, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

|

| Scenery, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

|

| Window View, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

But if I just consider the feeling I get from looking at the images in Arab Spring Dance, I find that I prefer to approach them from the perspective of Jungian psychology, which attempts to get at the elemental forces at work in the human psyche, what he called the archetypes of the collective unconscious. From this perspective, the Orientalist dancer is a specific cultural manifestation of the feminine principle which Jung called the anima. The complement to the anima is the male principle which he called the animus. Both these principles are at work in men and women. A man is influenced by an inner anima, and a woman by an inner animus. Keeping these forces in balance is a key part of any individual’s maturation into wholeness. We can also consider the need of a whole culture to keep these two forces in balance and properly assimilated into consciousness in a positive way.

The dancing girl, the Belly Dancer is the youthful, erotic stage of the anima. It is a basic, life-affirming force that opens toward joy, exuberance, and falling in love. In the Tantric traditions of India, we see it expressed in the friezes that decorate certain temples where it is identified with an energy called kundalini that can travel up the spine animating the whole body—an energy very much related to the impulse to dance. The potential for ecstatic release is built into our biology and can manifest in the higher emotional and thinking centers, spiraling up through the chakras to the crown. The anima is the soul, an inner guide ultimately to transformation and the wisdom of maturity.

Given this perspective from deep psychology, it is interesting to note that a number of the images of dancers used by Nour Ballouk are from a historic ballet adaptation of Rimsky-Korsakov's symphonic poem, Scheherazade, composed in 1888 and premiered as a choreographed dance by the Ballets Russes in Paris on June 4, 1910. It is based on the tale of One Thousand and One Nights, sometimes known as The Arabian Nights.

|

| Grey Dance, The Arab Spring Dance, 2015 |

The story line is like an Oriental fairy tale or myth that lends itself so well to a Jungian interpretation that I want to summarize it. Shahryar, the Persian King, after discovering that his first wife was unfaithful to him, resolves to marry a new virgin each day and behead the previous day's wife so that she would have no chance to be unfaithful to him. He had killed 1000 such women by the time he was introduced to Scheherazade, the vizer's daughter. Besides being beautiful, she had read and absorbed the books, annals, and legends of preceding kings and antique races, memorized the works of poets and knew the arts and sciences as well as philosophy. She was a great story teller, and the King lay awake and listened with awe as she told her first story, but she left the story unfinished to carry over to the next night. At the end of 1001 nights, she ran out of stories, but by then the King had fallen in love with her and made her his Queen.

Scheherazade in this tale is a fully developed anima figure with the power to effect a transformation in a king who is a monstrous animus figure. She becomes the very necessary guide to his inner world, leading to a change of heart. It is his, the King's destruction, that we see in the background photos to the dancers in Arab Spring Dance.

In Nour Ballouk's early work in oil and acrylic, she demonstrated mastery of classical figure rendering and began to announce the themes that she would pursue in her maturing work: feminine power and sensitivity and a romantic sensibility that is drawn to ancient occult teachings and symbols.

I note in particular a painting titled LABYRINTH in which the ancient image of a labyrinth is superimposed over the image of a woman in profile in the position of her heart.

|

| Labyrinth, Oil on Canvas 2013 |

She looks toward the image of a rooster in the background, clearly a male or animus symbol. The labyrinth creates, orders and protects the center (here the heart of the feminine) by conditioning entry. Entry into the labyrinth is an initiation, a step on the path of knowledge. But before knowledge is revealed, the old preconceptions must be dissolved by re-entry into the preformal state of the womb. This is Jung's journey toward wholeness, from the little self, to the Self of the fully developed human. At the center of the spiral labyrinth, man meets, overcomes and assimilates the monster, the Minotaur of his own hidden nature. The center of the labyrinth is thus a symbol for the state of balance.

I have said that a true symbol is so rich with meanings that it cannot be exhaustively rendered into words. Art is its own language, and we are lucky to have artists like Nour Ballouk to give us art symbols worth pondering and wondering about, symbols I believe with the healing power of the feminine.