Thursday, March 31, 2011

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

Jaffa Agricultural Orange Farms , FarhatArt Museum Collection

ا 30 أذار ا نحتفل مجددا بيوم الأرض أحببنا مشاركتكم صور زراعة الليمون في يافا قبل الإحتلال الأسود , الصور المعروضة من مجموعة متحف فرحات

30 March Is the"Land Day"of Palestine,Land Day is a day we all participate in because it is the day of the Palestinian people & their land.It is a day to commemorate & a day of tribute to those who... fell for Palestine,for the land and for the national identity.

30 March Is the"Land Day"of Palestine,Land Day is a day we all participate in because it is the day of the Palestinian people & their land.It is a day to commemorate & a day of tribute to those who... fell for Palestine,for the land and for the national identity.

Monday, March 28, 2011

Saturday, March 26, 2011

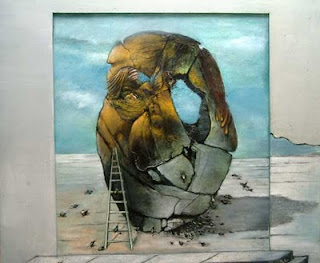

Gerardo Gomez Pop Art , Farhat Art Museum Collection أعمال الفنان جيراردو غوميز من مجموعة متحف فرحات

SONG FROM EL SALVADOR

OR : SONG "BAD BOYS" BY BOB MARLY

OR : SONG "BAD BOYS" BY BOB MARLY

Friday, March 25, 2011

Thursday, March 24, 2011

قساوة تشكيلية جارحة على ايقاع الجمال الانساني : أعمال عدنان يحيى بقلم لمى فواز

الجاذب في لوحات عدنان يحيى التي تحمل في مكامنها مذاهب و دلالات و مدارس رمزية و تشكيلية متعددة ان في رمزيتها أو مقاربتها للنحت أو في لحظها فن الكاريكاتور أن لها فاعلية واضحة من التجديد,و هذه قد يصعب الجمع بينها في معرض واحد و في صهرها و دمجها,حيث استطاع يحيى أن يتجاوز هذه المعضلة الفنية على وقع قسوة و حرارة موضوعه الانساني الذي بقي هو الكائن الحقيقي للوحة,و هنا مرارة يحيى في اختزال عمله المتعدد المذاهب و تذويبه في القضية الانسانية حيث المعنى يسبق الصورة ,ما يفيدنا من أن حساسية الموضوع و مرارته الانسانية رشحت من لوحته التشكيلية ما انعكس على المتلقي سهولة في كشف وجع اللوحة الانساني القائم على تناقض مذهل و مخيف بعدم التساوي الانساني.

المهم في سيرة عدنان يحيى أن قضيته الفلسطينية لم تحول لوحته الى خطاب سياسي مباشر لا بل عالج هذا الموضوع أولا بمفهومه الانساني دافعا به الى أقصى درجات الفن,و قد مزج القلق بالرموز,ليعبر عن انفعالات و خلجات النفس البشرية المتألمة و ما تعانيه من قلق و صراع,فجاء فنه كرسالة للعالم الخارجي:في هذا العالم ظلم..قساوة..ألم و دمار...

من يتأمل في لوحات يحيى,انما يتأمل في تاريخ شعب بأكمله.فتجربته الانسانية مشبعة بالذكريات و بتسلسل الأحداث:المجازر التي شهدها,التهجير,القتل ,النفي..الاضطهاد و الظلم المتواصل عبر عنها يحيى بالرموز و الخطوط و الألوان التي تبدو لاذعة و محرقة أحيانا,و ساخرة كاريكاتورية أحيانا أخرى,و مجدولة على ذاتها ككتلة مشدودة يتداخل فيها التشكيل بالنحت لتأتي كأنها عمارة فنية مجسمة و منمنمة بأناقة القساوة الجمالية الجارحة.

من يتأمل في لوحات يحيى,انما يتأمل في تاريخ شعب بأكمله.فتجربته الانسانية مشبعة بالذكريات و بتسلسل الأحداث:المجازر التي شهدها,التهجير,القتل ,النفي..الاضطهاد و الظلم المتواصل عبر عنها يحيى بالرموز و الخطوط و الألوان التي تبدو لاذعة و محرقة أحيانا,و ساخرة كاريكاتورية أحيانا أخرى,و مجدولة على ذاتها ككتلة مشدودة يتداخل فيها التشكيل بالنحت لتأتي كأنها عمارة فنية مجسمة و منمنمة بأناقة القساوة الجمالية الجارحة.

|

| قانا , عدنان يحيى , مجموعة متحف فرحات |

أما في الخزفيات فقد اتجه الفنان التشكيلي الى لغة نصبية خزفية عامودية التشكيل مبنية من الأسفل الى الأعلى مرتكزا على مجازر تاريخية ارتكبت بحق الفلسطينيين و اللبنانيين(غزة-قانا-جنين-القدس-صبرا و شاتيلا,وخزفيات مستوحاة من قصائد الشاعر الراحل محمود درويش).

|

| عدنان يحيى , مجموعة متحف فرحات |

هذه الأنصاب اعتمد الفنان على بنائها تدريجيا من قاعدة حولها الى شاهد قبر مذكرا بتاريخ المجزرة معتمدا الألوان القاتمة للدلالة على الواقع المأساوي لهذه المأساة,ثم شيد فوقها منصة متصلة تشي بتحول من جراء هذه المأساة الى حروفية متشظية كما في نصب-قانا-و نصب-جنين- المتشابهين في التأليف ووحدة الموضوع ليشيد في أعلى الأنصاب هذه آنيات متنوعة لكل مدلولها التفاؤلي المتصل بالضوء و الخروج الى الأمل و الى الحياة لاعادة رفض الظلم و القهر الذي لحق بأطفال و نساء و شيوخ القضية الفلسطينية و اللبنانية.ففي لوحة قانا الآنية التي جاءت على شكل تمثال الحرية الذي يمثل العالم الحر و التي تحولت الى خوذة عسكرية باسمها ترتكب المجازر بحق الطفولة و الانسانية,بينما الآنية في نصب جنين حولها التشكيلي يحيى الى جغرافيا أرضية و الى طائر يستغيث الى سماء,بينما حروف جنين تتشكل كخارطة أمل لفلسطين,أما في نصب القدس يستغل الحرف للدلالة القسوى على عروبة القدس من خلال صياغة حروفية تاريخية و محولا الآنية العليا بتجريدها الدائري الى قبة تجريدية دائرية,و كذلك في الخزفيتين المستوحاة من شعر درويش.أما نصب صبرا و شاتيلا و التي تمثل و تجسد فكرة الفنان التشكيلي يحيى و ان بمقاربة قاسية و جميلة مختلفة عن الآنيات التي ذكرناها,بحيث نرى الآنية الخزفية تتصدع لتخرج منها اليد الطينية البيضاء و كأنها تبعث من جديد للبحث عن حقيقتها ضد الموت الظالم.

ينحو التشكيلي يحيى في نصبه الخزفية الى تشكيل جديد غير مألوف,فالنصب عنده خارج اطار الجمال المعلق في الفضاء ,لا بل اتخذ منحى و توجه مرتبط بمجازر وقعت ضد الانسانية و أعاد تشكيلها من تحت الى فوق,من موت الى أمل,من قهر الى حقيقة...كأنه يعيد تشكيل المأساة بأمل جديد.

لوحات و خزفيات التشكيلي عدنان يحيى طالعة من تجاربه و مراحله المتصلة بدراسته ووعيه و يده,ما جعل من معرضه تجربة تتشكل كمحطة بارزة في مسيرته الفنية المصاغة بتقنية عالية

لمى فواز - فنانة تشكيلية

ينحو التشكيلي يحيى في نصبه الخزفية الى تشكيل جديد غير مألوف,فالنصب عنده خارج اطار الجمال المعلق في الفضاء ,لا بل اتخذ منحى و توجه مرتبط بمجازر وقعت ضد الانسانية و أعاد تشكيلها من تحت الى فوق,من موت الى أمل,من قهر الى حقيقة...كأنه يعيد تشكيل المأساة بأمل جديد.

لوحات و خزفيات التشكيلي عدنان يحيى طالعة من تجاربه و مراحله المتصلة بدراسته ووعيه و يده,ما جعل من معرضه تجربة تتشكل كمحطة بارزة في مسيرته الفنية المصاغة بتقنية عالية

لمى فواز - فنانة تشكيلية

Male Costumes, Arab Orientalist Photography, Farhat Art Museum

أنا لحبيبي وحبيبي إلي لا يعتب حدا ولا يزعل حدا أنا لحبيبي وحبيبي إلي

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Suzanne Klotz Neo-Orientalist & Political Art ,From The Farhat Art Museum

Suzanne Klotz Neo-Orientalist & Political Art ,From The Farhat Art Museum Collection , Get Up Stand Up By Bob Marly

فن سوزان كلوتز السياسي والمناهض للصهيونية من مجموعة متحف فرحات

"....Suzanne Klotz’s socially relevant mixed media works seduce viewers with their lush surface rendering, deft puns and symbolic use of materials, yet overwhelm with their carefully researched facts and figures. Banal objects from pop culture, military culture and daily use are transformed by a keen sense of social irony to complicate their consumer-driven surface illusions and more readily locate the less visible truths lying beneath their luscious façades. These thought-provoking images reveal a vivid commentary on the events of our times, conjure a haunting vision of a world without reason, and remind us that an understanding of the past is crucial to our present and future. Her works prompt us to reexamine our values, social behaviors and morals and they reflect, in an ironic way, the misconceptions many Americans have about America’s role in global society. They demonstrate a way to continue being critical, forceful and penetrating without hatred and without marked disrespect for the religious convictions of diverse believers and non-believers alike. The exhibition seeks to create awareness and dialogue about human rights abuses, examine the impact of military invasion and occupation, and explore relationships between social and personal accountability and power..."

Dorothea Barhonihttp://farhatartmuseum.inf

http://farhatculturalcente

Monday, March 21, 2011

غياب الفنان عدنان المصري / كحل عيوننا بالحرف العربي, أحمد بزون

|

| عدنان المصري , من مجموعة متحف فرحات |

ارتاح قلب الفنان عدنان المصري، بعد ضعف لازمه سنوات، لم يتخلّ خلالها عن عادته الدائـمة في متابعة الحركة التشكيلية في لبنان، وقد كنا نلتقيه في أكثر المعارض في بيروت وخارجها، نسمع آراءه الجريئة، التي يتحفظ في الإفصاح عنها أمام صاحب المعرض.

كان مهموماً بالفن، لكن كأنه فن الآخرين وملكهم، أما هو فمقلّ في نتاجه وفي معارضه، ومكثر من التمتع في جماليات سواه، بل ربما كان من أكثر الفنانين اللبنانيين انغماساً، أو حتى هوساً، بمتابعة جديد الفن التشكيلي.

لم يكن حيادياً أمام التيارات الضاجة في الساحة الفنية، فهو منذ البداية اختار أن يتخذ موقعاً للوحته، لم يحد عنه حتى آخر أيامه، وإن كان ينوع فيه ويشكّل داخل جدرانه. وهو من جيل كان عليه أن يؤسس للفن الحديث، واحد من الجيل الأول الذي تخرج من معهد الفنون الجميلة التابع للجامعة اللبنانية، ويعد من الجيل الثالث في الفن التشكيلي اللبناني. لم يكتفِ بدراسته بداية في الأكاديمية اللبنانية، وكان انتقاله من الأكاديمية إلى المعهد خير دليل على ولعه بالفن.

لا شك في أن العديد من الفنانين اللبنانيين فُجعوا بخبر وفاة عدنان المصري، ذلك أنه كان محبوباً وقريباً من الجميع، وهو الذي استمر في خدمتهم متنقلاً من هيئة إدارية إلى أخرى في جمعية الفنانين اللبنانيين للرسم والنحت، إذ لم تكن لتستغني عنه التشكيلات المختلفة فيها، فهو النشيط المتابع الحاضر الجاهز لأي مشاركة أو دور للجمعية، وقد كنا نسميه «الجندي المجهول» في الجمعية، لكثرة ما يعمل في سبيل الجميع من دون تأفف.

لا يمكن ونحن نتذكر عدنان المصري إلا أن ننتبه إلى أننا كنا أمام فنان مثقف يعرف ما يفعل، من دون كثير اهتمام لما يفكر فيه الآخرون، إذ لم يكن بالخفة التي تجعله يميل مع تيار هنا أو مدرسة هناك، فهو لم يختص بالفن وحده، إنما كان يحمل أيضاً ماجستيراً في فلسفة الجماليات. لذا طلّق المصري أعماله الأكاديمية، لينطلق بمشروعه الفني في بداية السبعينيات، مواكباً حركة تشكيلية عربية نشطت في تلك الفترة هي الحروفية. تلك المدرسة التي وجدها عدنان المصري متوافقة وأفكاره العروبية، من جهة، أو الأفكار التي تؤكد ضرورة وجود هوية فنية لدى الفنانين العرب.

|

| عدنان المصري ,من مجموعة متحف فرحات |

قد لا نكون مع الاتجاه العــام لفناننا الراحل، إلا أننا لا بد من الإشارة إلى ما فعله من تجديد في اللوحة الحروفية، إذ كان يجتهد دائماً مــن أجل ألا يكرر تجربة أحد، فهو لم يذهب إلى التعبــيرية التـي اتكأت على الحرف العربي كحجة وفاضت عليه حتى جعلته مجرد علامة شكلية خرساء، إنما عمل على البحث عن هندسة اللوحة الحروفية، إذا جـاز التعبير، عندما اختصر الألوان الحرة الفالتة، ولجأ إلى تكوينات للخط، تبقي على الكلمة ومعــناها، لكنها تذهب في المعنى نحو العمق أو الروح، لا نحو التصوير الذي يؤكد شكلاً خارجــياً، فهــو في الأساس ابتعد عن تصوير الطبيعة أو المشاهد الواقعـية أو الناس أو الأشكال التي تتحرك على الأرض، مقابل أن ينطلق نحــو الداخــل، في سفر أقرب إلى السفر الـصوفي. إنها الرحــلة التي تــنطلق على دفعات، حتى أننا نتطلع إلى لوحته الحروفية، فنجد كيــف تمـوج الحروف دفقاً بعد آخر، لتزاوج بين العين والعقل، مع غلبة الأخير بالطبع.

لم يستطع المصري الهرب بعيداً من المرئي، إذ لم تكن ألوانه مجرد موج يخرج من داخله فقط، إنما كنا نرى الطبيعة أحياناً وقد لبستها الحروف، هنا يموج الأحمر وهناك يموج الأصفر، وهكذا تتحرك الألوان مضيئة وساطعة وقوية، كأنها ملفوحة بشمس، أو غامقة وهادئة ملفوفة بالحزن أو الحكمة، نتنقل بين لوحة وأخرى كأنما ننتقل من فصل إلى آخر. اللون لديه بعيد عن الغيبية، إذ تجمع لوحته، إلى روحانيات التصوف، بعض الحسية. تتشكل الألوان صافية في مساحة اللوحة، بلا تظليل أو تقميش، فالحركة للخط والحرف والشكل الهندسي، فنجد المربع والمثلث وما إلى ذلك من هندسيات تستقيم مرة وتنحرف أخرى. حتى تصبح اللوحة لديه اختصاراً لعناصر التراث العربي الإسلامي كلها، ففي لوحة من أخريات لوحاته، شاهدناها في معرض مشترك أقامه المصري مع الفنان فريد منصور الذي رحل منذ شهور، نرى الشكل الهندسي، والحرف العربي والأرابيسك معاً، كلها تتقاطع وتتفاسح في رقصة فاتنة، لا يربكها التكثيف.

في أي حال، لم نكن نرى أعمال المصري إلا في معارض مشتركة، نقارنه بسواه، نراه دائماً مفرقاً، إذ لم نرَ له معرضاً واحداً يستعيد فيه تجربته، حتى ننتبه أكثر إلى المراحل والتحولات... لكن رحيله وضعنا أمام صوره مجتمعة، صور أعماله وصوره التي سوف تبقى مضيئة في عيون الجميع.

أحمد بزون

السفير

Sunday, March 20, 2011

Ayman Baalbaki: An Exploration of Self through the Experience of War

An Exploration of Self through the Experience of War by Sulaf Zakharia September, 2008

'I am part of a generation of artists and writers who lived 20 years of it and don't have anything to say but about war.'

Ayman Baalbaki was born in 1975, the year the Lebanese Civil War started. It is therefore no surprise that he draws his inspiration from war and the related themes of destruction and loss, emptiness, both emotional and physical, retribution and the identity of the victim. Intensely personal and highly cohesive, his latest exhibition at Beirut's Agial Gallery is marked by the same candor and vulnerability that has defined his previous shows.

In a 2006 interview, Baalbaki stated, 'The Lebanese don't want to address the issue of the war.' It is this denial that he challenges and confronts in this exhibition, in much the same way that Anselm Keifer, who clearly inspires his style, controversially challenged Germany's collective silence on the issues of the Second World War and the Third Reich.

The exhibition is neatly, almost clinically, separated into two distinct bodies of work, the portraits of dead buildings and those of masked men. Wake Up Sisyphus symbolizes the process of transition from one part of the exhibition to the other.

This brightly coloured installation constitutes a gentle visual bridge between the two parts of the show. Against the backdrop of a building in downtown Beirut, colourful family belongings are packed, and along with rural pets, seem to be ready for the start of a trip. The bright blue sky filled with red flowers is reminiscent of summer holidays in the village.

However, the gaiety of the work belies its poignant autobiographical content, its darkness almost immediately betrayed by its title. Just as the ancient Corinthian king was condemned to perpetually push a rock up a hill in Hades only to have it roll down each time it reached the top, so too has Baalbaki been condemned to continual displacement every time he settles.

Baalbaki's family was forced to flee Rass-el-Dikweneh by the outbreak of civil war in 1975. He was only a few months old. They moved to Wadi Abu-Jmil in downtown Beirut, a neighbourhood which became a refuge for those displaced by the war. In 1995 the Baalbakis moved out of Wadi Abu-Jmil to make way for the post-war wave of urban development and the artist experienced a sense of displacement for the first time. This time they moved to Haret Hreik. Five years later, Baalbaki moved to Paris where he lived till 2004 and continued to travel between Beirut and Paris till 2007. In 2006, the Israeli attack on Beirut destroyed Baalbaki's home in Haret Hreik along with all his belongings. It is this event that has inspired much of Baalbaki's recent art.

Abbas al Mousawi Street, Yassine Building and Untitled capture not only the physical but also the psychological devastation of the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon. Bold, almost violent neo expressionist brush strokes form dark, featureless buildings, partially or completely destroyed, devoid of life and bleeding, looming against grey skies and dominating the canvas. The plurality and the diminutive size of the paintings that make up Untitled undermine the significance of the destruction of any individual building and in so doing, underscore the true magnitude of the devastation and exacerbate the sense of loneliness and alienation. Equally devastated and devastating is the comparatively monolithic Abbas al Al Mousawi Street, Yassine Building, the subject of which was once the artist's home and studio.

Baalbaki's buildings are conspicuously devoid of human life which appears to have fled, taking up residence in the second half of his exhibition. But the humanity that emerges after the devastation has been altered by the war. The young men are either wholly or partially masked and women, children and old men are totally absent.

In Eye for an Eye, the viewer is confronted by 15 portraits of masked young men, (perhaps self portraits), whose faces are hidden behind a variety of masks, all associated with war: the traditional kaffiyeh, the war helmet, the gas mask and the ominous hood.

Baalbaki's use of masks is a complex, multifaceted one. Unlike the classical masks of Rome and Greece, his masks obliterate facial features and thereby hide any visible indication of emotion. Instead, it is his choice of mask that conveys the emotions hidden behind it. One does not need to see the face under the hood to know it hides unimaginable terror.

In his constant working and reworking of this motif, Baalbaki's masks have ceased to be mere devices for protection or the maintenance of anonymity. They have taken on a more fundamental function. He now uses his mask in the same was as primitive cultures used theirs, to mark a shift in a group's equilibrium, particularly in terms of its relationship to death . In this case, his masks have only emerged in the aftermath of the death and devastation of war.

The kaffiyeh figures prominently in Baalbaki's portraits. When he first started painting his kaffiyeh portraits, viewers misread the subject as Palestinians although he was painting faces that were also very much a part of the Lebanese Civil War. With the Intifada and the war in Iraq, his kaffiyeh-covered faces took on a broader Middle Eastern rather than a Lebanese or Palestinian identity. In Eye for an Eye, he presents the dichotomy of the kaffiyeh by positioning it alongside portraits of soldiers in gas masks and war helmets and war victims in hoods. Like Tarek Al-Ghoussein in his Self-Portrait Series , Baalbaki's use of the kaffiyeh is a direct challenge to the contradictory interpretations that have become attached to what was once a humble headdress used to protect the wearer's face from raging desert sands.

The portraits in this installation are mounted below a half open shutter, as if hung in a shop window. The words Eye for an Eye in Arabic script hang above the portraits, a clear demand for retribution. Part of an ongoing experiment with surfaces that have 'a local uniqueness' , Baalbaki paints the shutter a bright gold, like the backdrop of a Byzantine icon, bestowing a certain beatification upon the young men with the silently defiant eyes. Perhaps he has finally answered Reem El-Jindi's question, 'Victim or terrorist?'

In God, Baalbaki once again draws inspiration from Byzantine iconography for the installation's gold background and its curved top that the he used because of its resemblance to the icon retable and the shape of a tombstone . His canvas, this time, is the top of a traditional vegetable cart. His lone figure looks up at the sky in resignation. Above him, the Big Dipper recalls a story from Arabic mythology of a funeral procession. The father, lying dead in the coffin (the pan of the Big Dipper), is followed by his sons represented by the three stars of the handle as they head in the direction of the North Star, their father's killer, to seek vengeance.

While images of images of war dominate the exhibition, to say that Ayman Baalbaki's theme is war would be a gross oversimplification. It is not the war that fascinates him, but rather its impact on the human psyche, and more specifically, his own. Despite his exploration of broad themes, Baalbaki's work remains to a large degree introspective in nature. His work poses the question, 'How has the war shaped who I am?' with as much emphasis as makes a statement of the impact on Lebanon and its people.

'I am part of a generation of artists and writers who lived 20 years of it and don't have anything to say but about war.'

|

| El Bab , Ayman Baalbaki , Farhat Art Museum Collection |

Ayman Baalbaki was born in 1975, the year the Lebanese Civil War started. It is therefore no surprise that he draws his inspiration from war and the related themes of destruction and loss, emptiness, both emotional and physical, retribution and the identity of the victim. Intensely personal and highly cohesive, his latest exhibition at Beirut's Agial Gallery is marked by the same candor and vulnerability that has defined his previous shows.

In a 2006 interview, Baalbaki stated, 'The Lebanese don't want to address the issue of the war.' It is this denial that he challenges and confronts in this exhibition, in much the same way that Anselm Keifer, who clearly inspires his style, controversially challenged Germany's collective silence on the issues of the Second World War and the Third Reich.

The exhibition is neatly, almost clinically, separated into two distinct bodies of work, the portraits of dead buildings and those of masked men. Wake Up Sisyphus symbolizes the process of transition from one part of the exhibition to the other.

|

| El Bab - Detail- |

This brightly coloured installation constitutes a gentle visual bridge between the two parts of the show. Against the backdrop of a building in downtown Beirut, colourful family belongings are packed, and along with rural pets, seem to be ready for the start of a trip. The bright blue sky filled with red flowers is reminiscent of summer holidays in the village.

However, the gaiety of the work belies its poignant autobiographical content, its darkness almost immediately betrayed by its title. Just as the ancient Corinthian king was condemned to perpetually push a rock up a hill in Hades only to have it roll down each time it reached the top, so too has Baalbaki been condemned to continual displacement every time he settles.

Baalbaki's family was forced to flee Rass-el-Dikweneh by the outbreak of civil war in 1975. He was only a few months old. They moved to Wadi Abu-Jmil in downtown Beirut, a neighbourhood which became a refuge for those displaced by the war. In 1995 the Baalbakis moved out of Wadi Abu-Jmil to make way for the post-war wave of urban development and the artist experienced a sense of displacement for the first time. This time they moved to Haret Hreik. Five years later, Baalbaki moved to Paris where he lived till 2004 and continued to travel between Beirut and Paris till 2007. In 2006, the Israeli attack on Beirut destroyed Baalbaki's home in Haret Hreik along with all his belongings. It is this event that has inspired much of Baalbaki's recent art.

Abbas al Mousawi Street, Yassine Building and Untitled capture not only the physical but also the psychological devastation of the 2006 Israeli war on Lebanon. Bold, almost violent neo expressionist brush strokes form dark, featureless buildings, partially or completely destroyed, devoid of life and bleeding, looming against grey skies and dominating the canvas. The plurality and the diminutive size of the paintings that make up Untitled undermine the significance of the destruction of any individual building and in so doing, underscore the true magnitude of the devastation and exacerbate the sense of loneliness and alienation. Equally devastated and devastating is the comparatively monolithic Abbas al Al Mousawi Street, Yassine Building, the subject of which was once the artist's home and studio.

|

| Farhat Art Museum Collection |

Baalbaki's buildings are conspicuously devoid of human life which appears to have fled, taking up residence in the second half of his exhibition. But the humanity that emerges after the devastation has been altered by the war. The young men are either wholly or partially masked and women, children and old men are totally absent.

In Eye for an Eye, the viewer is confronted by 15 portraits of masked young men, (perhaps self portraits), whose faces are hidden behind a variety of masks, all associated with war: the traditional kaffiyeh, the war helmet, the gas mask and the ominous hood.

Baalbaki's use of masks is a complex, multifaceted one. Unlike the classical masks of Rome and Greece, his masks obliterate facial features and thereby hide any visible indication of emotion. Instead, it is his choice of mask that conveys the emotions hidden behind it. One does not need to see the face under the hood to know it hides unimaginable terror.

In his constant working and reworking of this motif, Baalbaki's masks have ceased to be mere devices for protection or the maintenance of anonymity. They have taken on a more fundamental function. He now uses his mask in the same was as primitive cultures used theirs, to mark a shift in a group's equilibrium, particularly in terms of its relationship to death . In this case, his masks have only emerged in the aftermath of the death and devastation of war.

The kaffiyeh figures prominently in Baalbaki's portraits. When he first started painting his kaffiyeh portraits, viewers misread the subject as Palestinians although he was painting faces that were also very much a part of the Lebanese Civil War. With the Intifada and the war in Iraq, his kaffiyeh-covered faces took on a broader Middle Eastern rather than a Lebanese or Palestinian identity. In Eye for an Eye, he presents the dichotomy of the kaffiyeh by positioning it alongside portraits of soldiers in gas masks and war helmets and war victims in hoods. Like Tarek Al-Ghoussein in his Self-Portrait Series , Baalbaki's use of the kaffiyeh is a direct challenge to the contradictory interpretations that have become attached to what was once a humble headdress used to protect the wearer's face from raging desert sands.

|

| Artwork By Ayman Baalbaki worked during the 2006 war on lebanon Farhat Art Museum Collection |

The portraits in this installation are mounted below a half open shutter, as if hung in a shop window. The words Eye for an Eye in Arabic script hang above the portraits, a clear demand for retribution. Part of an ongoing experiment with surfaces that have 'a local uniqueness' , Baalbaki paints the shutter a bright gold, like the backdrop of a Byzantine icon, bestowing a certain beatification upon the young men with the silently defiant eyes. Perhaps he has finally answered Reem El-Jindi's question, 'Victim or terrorist?'

In God, Baalbaki once again draws inspiration from Byzantine iconography for the installation's gold background and its curved top that the he used because of its resemblance to the icon retable and the shape of a tombstone . His canvas, this time, is the top of a traditional vegetable cart. His lone figure looks up at the sky in resignation. Above him, the Big Dipper recalls a story from Arabic mythology of a funeral procession. The father, lying dead in the coffin (the pan of the Big Dipper), is followed by his sons represented by the three stars of the handle as they head in the direction of the North Star, their father's killer, to seek vengeance.

While images of images of war dominate the exhibition, to say that Ayman Baalbaki's theme is war would be a gross oversimplification. It is not the war that fascinates him, but rather its impact on the human psyche, and more specifically, his own. Despite his exploration of broad themes, Baalbaki's work remains to a large degree introspective in nature. His work poses the question, 'How has the war shaped who I am?' with as much emphasis as makes a statement of the impact on Lebanon and its people.

Thursday, March 17, 2011

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Conditioned Humans or The Human Condition? Satirical Humor in the Works of Suzanne Klotz

|

| American Boy Bed, Suzanne Klotz, Farhat Art Museum collection |

You can't make up anything anymore. The world itself is a satire.

All you're doing is recording it.

– Art Buchwald, American political satirist

and Washington Post columnist

Humor’s cultural importance as a tool to disarm, teach, and open up possibilities for willing and constructive interactions, is summed up in an early statement by the philosopher Plato: “Serious things cannot be understood without laughable things.”1 In contemporary society, the roles the arts perform within culture have been limited too often to entertainment and aesthetic functions only. But the more challenging roles of art to culture are its civic, social and educational functions. Culture shapes the way we view the world. In a country that protects freedom of speech, yet lives with daily censorship of its people and its journalists for fear of immanent terrorism, and whose primary ethos has become unmindful consumption, the vital purposes for art making and viewing are too frequently forgotten, misunderstood, undervalued, or regarded with utter suspicion. Art that makes use of satirical visual humor therefore goes down like a sugarcoated pill, giving viewers greater incentive to pay attention to, and understand more deeply, the serious things, while laughing all the more ironically at the comedy of errors that is the human condition.

|

| Shuhada, Suzanne Klotz, Farhat Art Museum Collection |

Arizona artist Suzanne Klotz’s socially relevant mixed media works seduce viewers with their opulent surface renderings, deft puns and symbolic use of mass-produced materials. Yet they also overwhelm with their carefully researched facts and figures. Banal objects from pop culture, military culture and daily use are transformed through her keen sense of social irony to complicate their consumer-driven surface illusions, and to more readily locate the less visible truths lying beneath their luscious façades. These thought-provoking images reveal a vivid commentary on the events of our times, conjure a haunting vision of a world without reason, and remind us that an understanding of the past is crucial to our present and future. Her works prompt us to reexamine our values, social behaviors and morals. They reflect, in an ironic way, the misconceptions many Americans have about America’s role in global society. They demonstrate a way to continue being critical and penetrating without hatred or marked disrespect for the religious convictions of diverse believers and non-believers alike. Her exhibitions seek to create awareness and dialogue about human rights abuses, examine the impact of military invasion and occupation, and explore the often complicated relationships between social and personal accountability and power.

Beneath these interconnected themes is a passionate commitment to human rights and a simmering outrage against hypocrisy and injustice. In Unclaimed Laundry, an inverted American flag (a symbol of distress and metaphor for an inverted democracy), a shredded Palestinian flag, and embroidered and découpaged hand towels, handkerchief, and pillowcases are physically suspended from a vintage American Cordomatic clothesline–implying they’ve been left to dangle from a naïve 1950s ethos of America’s place in the global order. Pink parrots flitter and alight in a Disneyesque parody of American suburban domestic order. Here she uses the images of one domestic reality to describe, by implied comparison, another shattered domestic reality, asking in the process: if we define ourselves according to a marketing myth, what kind of worldview has it conditioned us to?

On closer inspection, the pillowcases on which we rest our heads, and the towels upon which we wipe our hands, image only chaos and the atrocities of war in the Middle East. Each laundered item on the clothesline addresses specific violations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The domestic iconography of “God Bless Our Home” and “God Bless Mommy and Daddy Forever”–sayings common to the American heartland–are here bitingly inverted and complicated by meticulously researched facts and figures. They detail the number of Palestinian homes destroyed in the heavily disputed 2002 “massacre” in the West Bank refugee camp of Jenin during the Second Intifada’s Operation Defensive Shield which employed modified military versions of the U.S. Caterpillar D9 armored bulldozers. Listed also are numbers of Palestinian males and children imprisoned without specific charges or trials. As a meditation on expanding meanings of “home,” it is clear in this satire of domestic family values that these same values are literally “hung out to dry” when applied to military aggression in other homelands. American dollar bills are tucked under the clothespins, presumably to reference the amount of unwavering diplomatic and material support, through taxpayers’ dollars, the United States provides the Israeli state and the related effort to spread “democracy” throughout the region. A small kerchief appropriates Disney characters to transform Mickey Mouse into a police officer holding a hula-hoop for Pluto to jump into while informing us that over 1,500 laws regulate daily activity in Palestine, like so many loopholes to jump through, “catch-22’s” to avoid and checkpoints that must be navigated daily. Knowing that American audiences have become numb and desensitized to the banality of human body counts, Klotz includes information regarding the bombing of a Gaza Petting Zoo, including an image of an ostrich with a leg blown off and a very angry teddy bear pondering the list of numbers of remaining victims. Poignantly, those two pink parrots that Americans so proudly display on the outer walls of their suburban homes pick up a double reading now as rosy escapees from that same bombed out Gaza petting zoo.

In Clean Sweep Settlement Extruder, an Electrolux vacuum cleaner refitted with mounds of concrete, rocks, bullet shells, gas mask and Israeli and U.S. flags, suctions a Palestinian flag through one hose while an “extruder” hose drops mounds of concrete representing new settlements. Cast iron praying hands atop the machine allude to nationalist objectives that masquerade in the guise of religion (the artist is always careful in her work to separate Judaic religious beliefs from Zionist political aspirations). The satire is distilled, compact and clear: a familiar household item is used to personalize the impact of the machinery of state that forces people out of their territory. Each of her works becomes a powerful indictment of man’s inhumanity to man.

Suzanne Klotz’s artworks draw from personal experience – she has witnessed the effects of military aggression on the families of both Palestinians and Israelis. Between 1990 and 1995, she was a repeated guest artist of Mishkenot Sha'ananim, a non-governmental International Cultural Centre in Jerusalem. Much of her time was spent in the West Bank and Israel, facilitating collaborative exchanges between Palestinian and Israeli artists, educators, and professionals, culminating in a landmark group exhibit at the Municipal Gallery in Jerusalem. She has been an eyewitness to events in the region only to see them misrepresented in the American media, and thus feels strongly that it is important for people to personally investigate truth in distant lands as well as in their own back yards. Her use of familiar household materials deliberately personalizes some of the 'unseen' aspects of war and questions the effects of military occupation not only on the forces involved but also on the family dynamics of societies at large.

|

| 99 Names of Allah, Suzanne Klotz, Farhat Art Museum collection |

By contrast, there is nothing satirical in her treatment of authentic faith. 99 Names is a series of ninety-nine handcrafted artist books, each referencing a separate attribute or virtue of God as recorded in the Qur'an. The books affirm the unity within the spiritual teachings of the major world religions and double as personal interactive journals for recording one’s private application of each virtue.

Another artwork made of multiples, Democracy Sampler (Cookies from the White House), consists of a U.S. Army-issued ammunition box, filled with ceramic stoneware “cookies” packaged in separate biohazard specimen bags. Each cookie represents a different chemical used in warfare in Iraq, it’s name printed on one of those little American toothpick flags like some dementedly cheerful American Diner home-cooked meal. The cookie names include: Nerve Gas, White Phosphorous, Depleted Uranium, Cluster Bombs, Napalm, and 70 tons of radiation poisoning. Facts and figures served up cold with such scathing parody are sobering, their impact palpably resonant.

In fearlessly tackling a wide array of inter-related issues in these works, Klotz suggests such follies are not limited to the Middle East but common in every civil society. Her urgent warning cautions that even to the victor will come ruin. By turns witty, grotesque and satirical, her intent is to create compellingly dissonant visual experiences that challenge aesthetic and intellectual complacency and expand social consciousness and awareness. In navigating the terrain between indifference and attentiveness, social conditioning and compassion, Klotz reminds us that art still provides humanity with a True North-seeking compass, and that hers can function as a willing magnetic north to conscience.

Too often, we tend to view artworks as completed solutions or answers, when in fact most artists see their works as questions posed to the cultures in which they live. In Family Ties, the questions are laser precise in their spiritual and ethical dimensions: how can our individual fears override our common humanity? How can unjust treatment of other human beings ever be justified? How do humans settle in their conscience questionable actions taken by governments elected to represent them? What do our tax dollars fund overseas? How do our noblest ideals fare around the world? Where is our collective voice of outrage? The exhibit provokes viewers into asking themselves internal questions for which there are no easy answers. Thus, these satiric works can run the risk of provoking viewers to an anger directed at the art or the artist for providing the stimulus. The more difficult next step is for viewers to interact constructively by asking themselves where they stand personally and what might they do? The cumulative effect of the work asks us to connect our own core humanity to that of these other cultures for whom American export culture and political decision-making translate into real daily social impact.

|

| Boogie Man Comforter, Suzanne Klotz, Farhat Art Museum Collection |

Viewing these works, we may laugh uproariously one minute, only to become embarrassed by our response the next. We may find the humor uplifting, or very nasty. Satire is thus a form of stealthy criticism. Because satire combines the outrage of truth with humor it can be profoundly disturbing. As is the reminder that this is the recording of real life, Klotz is not making this stuff up, each fact is carefully researched from multiple reliable sources. If the world itself has become a satire, a satirical art of civic engagement needs to disturb our deep indifference and complacency, but not in order to make us feel bad about ourselves. Rather, precisely in order to create spaces where we think more deeply and feel more sharply what American ideals, rights, privileges and our roles as American citizens mean, and not in simplistically conditioned ways, but under difficult conditions. If you don’t laugh, you miss the point. If you only laugh, you miss your chance for deeper meaning and illumination.

Klotz’s satire reminds us it’s not ok to escape from everything else all of the time, as the consequences often come back to roost. She brings a sober awareness that the world can’t fade into the background forever, like some convenient exotic Hollywood location. Often she makes her point by pushing the satire over the top where we no longer laugh, provoking viewers into extreme cognitive discomfort. In those moments the cynical overtone evidences the artist knows it’s futile to think she might correctively restore paradise to earth through her artworks. At best she is aware that, although she may hope to reform and restore through her art, she can guarantee only to expose vice and hypocrisy, to make them sufficiently repulsive through the shock of recognition, to simply slow the course of greater evil. What happens when we can no longer laugh while viewing her work? When we feel so traumatized by the revelation of our own conditioning we don’t know whether to laugh or cry? For starters, we begin to think, to become more deeply attentive, possibly to anger, and perhaps to begin to passionately desire an alternative outcome than that represented in her imagery, the imagery of a, by now, surreal human condition.

The book publication and exhibition title, Family Ties Occupied Art, implies that the foundation of a society is in the strength of its family bonds, which comprise the strength of the community, however families and communities are defined most broadly. By extension, the strength of a nation is dependent on its ability to interact with other nations. The larger implications regard the greater human family to which we all belong, and thus we are all implicated in this global satire together. From the conditioned nursery rhymes we sing as children, to the Proud To Be American t-shirts and hats we wear, to the foreign-made products we eagerly consume, those taxes we pay as good citizens and all the gas burned on family trips to other countries and cultures–we are all in this human condition together, for better or for worse! So what will be the quality of the experiences we record?

Sophia Isajiw, MFA

Independent Arts Writer/Curator

©2013

Saturday, March 12, 2011

Friday, March 11, 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)